IITTALA KALEIDOSCOPE: FROM NATURE TO CULTURE This exhibition is a celebration of Iittala’s 140-year history. Such historical progression does not follow a linear path but rather a complex network that is deeply interwoven with Finland’s 20th-century geopolitical and socio-cultural conditions. Founded as a glassworks in 1881, Iittala soon became immersed in the core of Finland’s industrial and creative development, while participating in the delineation of the design field of the Nordic region. Today, evolving perspectives introduce new questions about design, ecology, manufacturing, craftsmanship, food cultures, rituals and living environments. Beyond contextual changes, the flux of aesthetic and ideological movements and consequential shifts in ways of life, the history of Iittala reveals a continuity of deep-rooted values connected to craftsmanship, creativity and social conscience, as well as the preservation of traditions linked to Finland’s inherent dialogue with nature. Kaleidoscope, as a term, means “beautiful form”. The exhibition’s thirty sub-themes shed light on the evolution of Iittala’s products from raw materials through creativity to production, the social impact of products, and ultimately product disposal, recycling or reuse. The exhibition concept, curation and design has been developed by the architect Florencia Colombo and industrial designer Ville Kokkonen. NATURE Learning from nature is an inherent quality of humankind. Observation of the natural world has been in Finland a reference of material resources, intelligent forms and processes as well as inspiration for creativity and expression. Nature is embedded in the history of Finnish culture. The scale of Finnish forests and lakeland provided ideal operational settings for the development of various industries. Metal, ceramic and glass were historically linked due to the country’s principal economic activity: forestry. Nature marks simultaneously the beginning and the end of a product’s cycle: from raw materials, energy resources to the disposal or recycling of matter. Shifts in the understanding of physical, aesthetic and symbolic material properties have existed throughout the human dialogue with the environment. In Finland, ideas of sustainability and recycling have been present throughout material culture history. Nevertheless, the notion of an object´s life cycle continues to shift according to evolving environmental, techno-industrial and sociocultural perspectives. MATERIAL VALUES Whether material values were practical and concrete or symbolic and imagined, they have always caused societal changes. The concepts of waste and recycling are a result of industrialization. Before the advent of mass-production, the prolonging of the life cycle of materials and objects was in Finnish material culture a natural process. Iittala’s recent developments in the use of recycled glass and the introduction of the Vintage program have contributed to a new system of values connected to environmental concerns. In 2019, Iittala was one of the first glassworks to manufacture products with 100% recycled glass. Global ongoing research addresses how the circular economy should be implemented integrating consumers, corporations, educational institutions and policymakers. MATERIAL RESOURCES The historical manufacture of glass is said to have first developed in Egypt and Mesopotamia as a form of glaze applied to ancient pottery. The development of clear glass appeared in Alexandria in 100 AD as a result of the addition of manganese oxide to the formula. The glass industry arrived in Finland through Sweden by glassblowers from Central Europe. The principal material for the manufacture of glass is quartz sand (silica). Coloured glass is created by incorporating specific compounds into the clear glass composition. Changes in material resources, formulas and fabrication techniques through time have determined the atomic state, structure and colour of Iittala’s glass, defining the specific functional and aesthetic properties of its products. MATERIAL BEHAVIOUR Glass is a metamorphic material. Its chemical composition is continuously manipulated for a range of different applications. In this sense, glass has the same capacity to be a source of engineering as it does to be a source of expression. Glass manufacture involves a dialogue between chemistry and physics. Glass is formed by taking melted silica and adding a flux, such as soda or potash that has been stabilized with lime. The flux makes the sand dissolve and fuse between temperatures of 1,000°C to 1,200°C. The chemical composition affects formal malleability, tint and general character. The history of Iittala encompasses many eras of glass formulas, each leading to distinctive material expressions. THOUGHT In Finland, material values in general —and that of glass in particular— developed with a logic of its own. The enigmatic nature that glass acquired throughout the 20th century was the result of the ingenuity and collaborative dynamics between industrial artists and craftspeople. Experimentation characterized a creative logic that resulted in an exceptional array of expressions, introducing glass to new meanings, functions and techniques. Throughout different eras, applied artists and designers contributed through their creativity to the development of Iittala’s distinctive creative profile. Since its foundation, Iittala’s system of operations around product development has evolved alongside changing contextual factors. The firm presence of arts and crafts and the interdisciplinary nature of education reflected in Finland a unique approach to the design field. Contrasting points of view questioned the role between applied artists and industry, giving impulse to unique academic, industrial and creative developments. Iittala’s 20th-century body of work is an illustration of this process. CALL FOR IDEAS Until the beginning of the 20th-century, equal models were produced by all Finnish glass factories. During the first half of the century, the search for new creative input was conducted through the organization of competitions. The 1932 Karhula-Iittala competition was considered a historical turning point in Finnish glass design and manufacture. The competition resulted in two principal outcomes: Aino Aalto’s pressed glass tableware series Bölgeblick and the appointment of Göran Hongell as Karhula glassworks’ artistic advisor. Karhula-Iittala’s 1936 competition was launched in response to the upcoming Paris World Fair in 1937. The 1946 competition was organized by Iittala, independently from Karhula, and aimed to provide new models for the upcoming Nordic Applied Arts exhibition in Stockholm. Wirkkala and Franck were subsequently hired by Iittala. FROM ARTS AND CRAFTS TO INDUSTRIAL DESIGN The first school of applied arts was established in Helsinki in 1871. From 1930s Arttu Brummer was a leading figure who brought academic training closer to practice, operating beyond education as a designer, curator and cultural critic. Term ‘design’ came into use in Finland in the 1950s and education in industrial design began in 1961. From arts and crafts, applied arts, industrial arts, to industrial design, parallel definitions were often used simultaneously marking ideological tendencies. The development of industrial design was accompanied by a shift in the dialogue between corporations, factories and designers. Alongside, new ideologies and new ways of working emerged, which reflected the changes taking place within society and culture. FORM GIVING Experimentation is an inherent property of glassmaking. The persisting element of craft involves a dialogue between the designer and the glassworks. The process behind the introduction of each new product or artwork is a complex collaborative equation with many contributors. The design-driven approach of glass factories was evidenced by the hiring of artistic advisors such as Göran Hongell at the Karhula glassworks and Erkki Vesanto at the Iittala glassworks. The appointment of in-house talent ceased during the early 2000s, in favour of collaborations with Finnish and foreign freelance designers. Despite the evolving relationship between designers and industry, Iittala’s experimental dynamic of collaborations allows designers to continue exploring the possibilities of glass with the support of highly skilled technicians and craftspeople. KALEIDOSCOPE It is impossible to grasp the essence of Finnish design without understanding the dialogue between its nature and culture. In the Nordic region, an ideological concept of beauty linked aesthetics to societal change. Beauty assumed, in this sense, a revolutionary character. Reflected in Iittala’s glass, Finland’s boreal ecosystem assumed a critical role in the creative language of many designers, embedded in their conceptual universe, artistic expression or interwoven in the stages of their creative processes. Glass informed a unique language of communication. The development of Finland’s 20th-century culture introduced new variables into the realm of glass, extending beyond the table to interiors and lighting. Meanwhile, the development of contemporary consumer culture introduced new modes of socialization and rituals, influencing formal and functional experimentation, the role of colour as well as the extension of Iittala’s material spectrum. Glass nevertheless remained at the core of the brand’s essence. MAGIC REALISM Magic Realism is an analytical category that developed throughout the 20th-century within international literature, painting and film. In the context of Finnish glass design in general – and the history of Iittala in particular – Magic Realism refers to the incorporation of a supernatural element in quotidian life; the incredible within the normal. Across Iittala’s history, beauty has fostered a dialogue between subjective poetics and socio-economic agendas. A deep relationship with the force of Finland’s environment, a material culture respectful of the country’s ancestral craft and the inherent sublime character of glass and glassblowing embedded Iittala’s works with a natural metaphysical spirit. Mythological imagery and formal rigor became interwoven with Finland’s supernatural conceptions of nature and matter. As a medium of expression, glass came to simultaneously embody reality and illusion. HISTORY AS RHIZOME From the fields of music to architecture and industrial arts the sublime is omnipresent in every layer of Finnish cultural expression. Creative fields constituted public channels for the construction of a collective identity. In this context, Iittala’s history illustrates the brand’s complex dialogue with Finland’s cultural, political, economic and social evolution. Design-driven industries became ideological pools and international marketing channels for the cultural and political promotion of Finland, first as an independent nation and later as part of the Nordic region. The introduction of modernism and the development of a functionalist regional perspective during the 1930s and 1940s set the foundation for Iittala’s forthcoming design principles. In this context, Iittala’s creative achievement is distinguished by the dichotomy between an endurance of skilled crafts and the influx of modern ideological and technological processes. CLIMATE AND CULTURE The experience of nature is culturally determined. Regional belief systems and mythologies developed as a means of understanding the surroundings. Survival and well-being were historically linked to the seasons, which represented a cyclic universal order. In Finland, perception has been influenced by nature. This represents an enduring quality that distinguishes Finnish culture from that of other nations. During the mid- 20th-century, this dialogue became a strategic rhetoric for international cultural-political propaganda. Mural-scale photographs showed environmental settings through aerial images of forests and lakes, which illustrated Finland’s sparsely populated landscape. Within Iittala, the temperament of the landscape became moulded onto glass. Whether informed by atmospheric conditions or cultural filters, the perception of nature has provided Finnish designers with a mastery of super sensorial attention. SOCIAL INDIVIDUALS Since launching, Kaj Franck’s tableware collection Kilta, and its natural successor Teema, has become a symbol of universal grammar. The design concept responded to the functional needs of Finland’s new masses. Taking into consideration versatility and costs, Kilta projected a normative rigour; all elements existed independently of the concept of collection but responded to a standard morphological family. Each component was individually developed to serve a wide range of purposes. The collection was first introduced in 1953. Despite achieving widespread success, Kilta was discontinued in 1974 and reintroduction under the new name Teema in 1981 with a complete technical redesign for its production in stoneware. Its universality has allowed elements to be used through time across different cultures and food traditions TRADITION AND MODERNITY The time frame and characteristics of Finnish industrial development enabled the persistence of handicraft skills. Until the introduction of mass-produced items, domestic artefacts in Finland displayed site-specific characteristics and an in-depth understanding of material resources. By the mid-20th century, social equality was a charged concept through which functionalism revived a folk ethos. Product types referencing vernacular material culture and the habits around their use remained a source of study and reference. Tradition and modernity do not constitute a binary distinction but rather a unique formula that characterized Finland’s distinctive design evolution. As a social and cultural system, tradition is a dynamic entity. To this day, a sustained respect for cultural ancestry is expressed, for example, through the revised interpretation of material resources, typologies and rituals. VISUAL SYSTEMS As a perceptual instrument, glass has had historically a significant impact on our dialogue with the world. Distortions in the surface of glass allowed new perspectives, encouraging glass to be used as a thinking tool. The functional application of glass evolved in parallel with its projected spiritual and aesthetic associations. The 1920s and 1930s are considered Iittala’s crystal age. Nevertheless, the cutting of lead crystal broke from its Bohemian origins and assumed a new abstraction. Glass facets began to project a graphic sense of vertigo, three-dimensionality and illusion. Optical qualities were since then creatively explored through further craft, technical and design variables, experimenting with the sense of perception and pushing the limits of glass as sensory experience. MIMESIS Observation of the natural world has been a source of intelligent forms and processes as much as it has been a resource for creativity and expression. Finland’s societal development reflects a sustained relationship with nature’s spiritual power and symbolic content. Throughout Iittala’s history, inspiration from the natural environment has given rise to sublime glass expressions. These unique manifestations of glass informed alongside a language of communication. Films, photography and exhibitions paid homage to nature’s beauty and intelligence. Each glass designer interpreted nature in a unique way. Through these works, organic and inorganic worlds display an effortless sense of beauty. They reveal the laws of nature, in particular, the essence of ‘life’. CERAMICS AND GLASS Ceramics and glass remained for a period of time parallel materials that demonstrated similar properties. In early objects, glass was translucent or opaque, a technique and character that has continued to be applied up to today. Since 1881 Iittala was in various ways linked with Karhula, Hackman, Arabia, Nuutajärvi, Rörstrand, Gustavsberg and Fiskars. Core values about glass and the skilled craft surrounding its manufacture remained fundamental principles. Nevertheless, each corporate transition contributed with new perspectives towards materiality. Ceramics were introduced into the Iittala product range in 2002, revising Iittala’s history of glass. The introduction created a new dialogue in what had been a specialized production environment. Glass was now approached as part of a larger constellation of materials and functions. DIFFERENCE AND REPETITION Stacking, seriality and layering, introduced new imaginative relationships between objects. A language of repetition emerged. Visual mediums became a mirror of the expressive power of the new industrial society. The emergence of experimental graphics and photography fused the spirit of serial manufacture and utilitarian norms. Abstract compositions and visual resources, such as positive-negative contrasts and montage, became linked to the serial nature of industrial production. The need for versatility and spatial efficiency developed a formal language based on the concept of seriality and assemblage. Designs began to incorporate distinctive solutions between the individual unit and the set. Utilitarian requirements became sculptural compositions and the resulting products provided both poetics and rigour. COLOUR Colour is a cultural phenomenon. Historical, environmental and affective themes influence the selection of specific hues. As a sensation, the way in which each person experiences colour is inherently connected to the dialogue between environmental and subjective variables. Throughout Iittala’s history, the production of colour has been associated with different socio-cultural, political and economic contexts. Today, Iittala is highly valued for its skilled knowledge of and affective approach to coloured glass. Nevertheless, there was a time when Iittala did not manufacture any coloured glass at all. Although there are thousands of colours in the archives, Iittala’s current palette consists of 200 colours, out of which an average of 20 are actively used annually. I-GLASS In May 1956, Iittala presented a new collection and strategy. Iittala’s i-glass exhibition, launched Timo Sarpaneva’s extensive i-line alongside new works by Tapio Wirkkala and Erkki Vesanto. The logo designed by Sarpaneva for the i-line later became the logo for the complete Iittala brand. The exhibition catalogue presented Iittala’s new direction as a glassworks and brand. By developing the i-line, Sarpaneva sought to explore lightness and colour. The omnipresent Nordic concept of ‘beauty for everyday life’ informed Sarpaneva’s functional approach. Utility goods were reinterpreted through artistic expression. Fragile abstraction was indicated by the use of a watercolour palette; the range developed specifically for the collection aimed to achieve a ‘broken’ hue. Sarpaneva worked with Iittala’s chemist Keijo Laitinen on a grey-based colour code that would allow the items to maintain a delicate and balanced composition at the table. GEOMETRY Since Iittala’s very beginnings, geometrical forms express attributes of nature, optics, formal universality or simple compositional whim. As a group, these geometrical works present an abstract composition and reflect a muted dialogue. They spark a sense of wonder yet maintain a silent beauty. They reflect a quiet, interior logic, a subtle common sense. Their simplicity derives from a poetic rigour. These items nevertheless do not belong to any particular common era, nor any common conceptual or creative universe. As with colour, geometry reflects through the work of each designer specific contextual variables connected to socio-cultural tendencies, formal and conceptual ideologies, as well as material and technical conditions. FLUID DYNAMICS In glass, there is a reciprocal choreography related to the natural fluidity of the material. Its Plasticity of glas enables the exploration of free forms. There is an interactive space between the affordances of the material and the creative intention. In this sense, glass has the quality to guide expression: it elicits an affective response, it creates expectation. Glass could be interpreted as the ‘fourth state of matter’; there is hardly any surface quality that it cannot assume. Dialogues between environmental water states and glass expressions reflect a ceaseless source of inspiration. In these, there is an element of psychophysics, which communicates certain sensorial and emotional values. Formal malleability, colour, texture, reflection, translucency and light transmittance express a sense of matter. TOGETHERNESS Home is a fluid concept. Its meanings are multiple and its boundaries dynamic. In the 21st-century, the domestic sphere has become part of our public virtual space as well. Through technology, spatial boundaries and human connections have become elastic. In the dialogue between material culture and the domestic and social sphere, artefacts connect us to space. They conform to a language that is personal, and yet is in dialogue with a cultural system. In Finland, the notion of togetherness is strongly felt in the connection between food and culture. Within this dialogue, objects have developed that are specifically meant for sharing meals and drinks. A sense of sharing remains an essential element of Iittala’s core to this day. ARCHETYPES Most of the objects that compose our surroundings and participate in our daily lives derive from ancient models. The term ‘archetype’ derives from a Greek term, made up of ‘arche’ (origin) and ‘typos’ (pattern, model). Archetypes may be interpreted as a universal formal response to a standard function. From a global perspective, they constitute a fragment of civilization’s historical, technical and material legacy. Archetypes reveal a depth of wisdom – an evolution of knowledge and skill that refines the essential properties of formal and functional solutions over time. A certain archaeology of design is recognizable in many of Iittala’s designs, taking reference from historical examples reflecting a sense of anonymity, universality, timelessness, functional precision and synthesis of form. ERGONOMICS Using kitchen utensils and engaging with tableware are natural daily behaviours. It is through these seamless routines that a design’s effective functionality is revealed. Ergonomic attributes provide comfort and efficiency in the execution of tasks. These repetitive motor sequences lead to the cognitive incorporation of tools to our anatomical spectrum. As a result, tools perform as extensions of our bodies. The publication of Darwin’s theory On the Origin of Species in 1859 has since prompted theories on the influence of tools in human evolution. Hand tools reveal a dialogue between musculoskeletal properties and biomechanics. Force, grips, precise movements, wrist rotations and the operation of elements between thumb and fingers reflect how the design of a tool accommodates to human form and motor skills. FOOD Food, together with its rituals, offers a lens with which to analyse society. It reflects the identity of a region and its community, including its local traditions and material culture. In Finland, certain utensils have even developed in correspondence to specific foods and drinks. Traces of these cultural practices and the wares made to facilitate them can be observed throughout Iittala’s history. More recently, the evolution of communal social patterns has introduced to Iittala new interpretations of the experience of a meal. Influences from local and foreign cultures are evident, along with the increase of nomadic ways of life and new domestic layouts adjusted to the introduction of technologies. Changes in lifestyle introduced new modes of food consumption, even new interpretations of food. COMMUNICATION The transmission of information through media has the capacity to shape values, opinions, desires and behaviour. In the dialogue between economy and culture, the engagement of mass media with design was, throughout the 20th century, a critical impulse in Finland for the establishment of design-driven industries and the creation of a modern consumer society. Mass manufacture called for mass consumption. The capacity of photography to express both physical and psychological perspectives allowed design to project attributes that lay beyond visual form. Imbued with the spirit of abstraction, certain design portrayals even assumed an international iconic status. Since then, the move from analogue to digital created a shift in the ways in which Iittala’s communication strategies are produced and consumed. TRANSFORMATION The manufacture of glass maintains a sense of wonder. At Iittala’s glassworks, members of the factory team reflect on the enduring existence of an element of ‘magic’. Form seems to be captured from an ephemeral moment. The level of creative input of the glassblowers reveals an embodied knowledge in which the choreographing process remains in intimate dialogue with physics and the material laws of nature. Glassblowers are, in this sense, an extension of the designer. They are interpreters of form. Their hands, eye, breath and mind guide the material. Through glassblowing, the hidden principles of glass are transformed into visible phenomena. Iittala’s manufacturing evolution has progressed alongside the development of production methods since the factory’s foundation. At present, production is divided between traditional blowing methods and automated processes. Craft is often interwoven with mechanical tasks. Throughout the 20th-century and up to present, mouldmakers, engravers and glassblowers have contributed to the definition of Iittala’s distinct character. MECHANIZATION Mechanization has been part of the Iittala factory since its foundation, starting with semiautomatic pressed glass using man-powered machines. Fully automated processes were introduced in Finland after the war years. The process of rationalization led to the eventual loss of knowledge about certain craft skills. Present automated manufacturing operations at the Iittala glassworks include pressing and centrifugal casting. The nature of the material always incorporates the imprint of its maker: machine or human. An item of glass is a direct result of its manufacturing method. From the development of machinery to moulds and glassblowing methods, innovation at the Iittala glassworks has been the result of the combined efforts of craftspeople, technicians and designers alike. NEGATIVES The quality of mid-century Finnish glass admired through exhibitions and media was the result of a frequently anonymous team of craftspeople and technicians. The interpretation of ideas often developed through mouldmaking. In certain cases, applied artists and designers – such as Tapio Wirkkala and Jorma Vennola – became involved in the development of their own moulds. Mouldmakers and glassblowers collaborate on the details required for a mould. Mouthblown products are still currently manufactured using either wooden, graphite or steel moulds, depending on the nature of the design. Products produced with steel moulds are always tested with wooden moulds first. CRAFTSMANSHIP Glassworks have historically operated as a community. Many of the masters began at a young age and remained in the factory until retirement. An in-house glassblowing training programme was created by Erkki Vesanto in 1954. After this vocational training system was interrupted, a collaboration was established in 1995 with the Kalvola Secondary School offering glassblowing as an elective. Many of Iittala’s current glassblowers stem from this programme. Glassblowing involves an intimate dialogue between the material’s malleability and a craftsperson’s visual and physical response. Glassblowers work in a team which proceeds with a rhythmic choreography. The steps required for each piece is embedded in much the same way as that of a musician and a score: glassblowers can recite the processes by heart. CULTURE Since its founding Iittala was woven into local and international events of historical and sociocultural significance. The development of industrialization, consumer society and urbanization processes were intersected by shifting political ideals. This led to a revised public and pedagogical role of the design field, channeling new aesthetics, functions and values. In this context, Iittala provided a platform for artists and designers to express themselves. These unique conditions gave Iittala’s creative output significant local and international attention. Glass assumed a new cultural value. As living standards began to rise, the development of a responsible consumer culture assumed a socio-economic agenda. Pedagogical programmes associated beauty and well-being to functionalist principles. Exhibitions, films and magazines participated in familiarizing the public with the universe of ideals, materials, and technologies promoted under the concept of the modern home. Design became a phenomenon of mass culture. The sum of these contextual elements delineated throughout the century Iittala’s dynamic conceptual, functional and aesthetic characteristics. POLITICS OF DISPLAY Finland participated in almost every world fair throughout the first half of the 20th-century. After its independence, sustained efforts reflected the need to communicate a strong expression of the country as a modern Western nation. In this context, the construction of a comprehensive cultural identity became a pivotal diplomatic manoeuvre. Through joint efforts between state and industry, design came to play a pivotal role and cultural entrepreneurs became influential diplomats of the field. Iittala often created original works for these international exhibitions. In this sense, exhibitions constituted a laboratory for the testing of ideas. The international recognition that these works received projected an aura and national popularity onto Finnish design, in general, and glass in particular. TIME AND LATITUDE Collections and exhibitions tend to mirror a scientific and cultural context, shaping as well how works are communicated to society. While the values of the Nordic ideal were in Finland evident in the concept of ‘beauty’, the indoctrination of global mass audiences to functionalist standards of taste became a phenomenon that was reflected through “good design” exhibitions. Today, the sum of these works are significant to history, while simultaneously absorbed by contemporary global social patterns. Recent changes in consumption behavior and design values have introduced a widespread acceptance of the circular economy and new interest in vintage items. This continuation of life cycles intrinsically responds to Iittala’s historical values. EVERY DAY EVERY MAN Finland’s socio-economic structure underwent substantial changes during the mid-20th century. Design concepts were founded on the needs of the new masses. Ellen Key’s pioneering essay Skönhet för alla (Beauty For All) was a key reference for the development of Nordic functionalist ideals. In this process, beauty became linked to the democratic spirit of collective well-being. The perception of society as a unit informed the role of design in industry and culture. Mass production was placed in dialogue with mass population and minimum dwelling, leading to the rise of standardization as an industrial system and a social dogma. A new sense of creativity and innovation emerged. The concept of ‘every’ – promoted through universal products – became a didactic design statement.

Pictures:

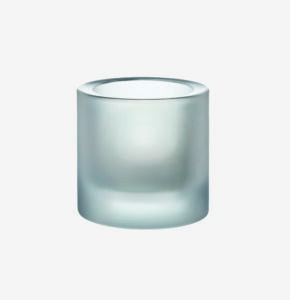

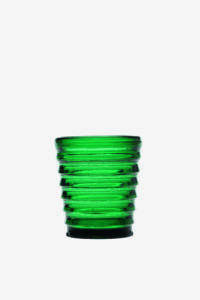

1 Stefan Lindfors Boy, glassware pressed glass 1998 Iittala Photo credits: Johnny Korkman 2 Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec Fleurs mouthblown, handcrafted glass, wrought iron 2020 Iittala 3 Erkki Vesanto carafe mouthblown glass 1954 Karhula-Iittala / Iittala glassworks Photo credits: Johnny Korkman 4 Jorma Vennola Prototype for Paula glasses 1975 Photo credits: Johnny Korkman 5 Carina Seth-Andersson Tools Seth-Andersson 98, serving bowl brushed stainless steel 1998 Photo credits: Johnny Korkman 6 Heikki Orvola Kivi (Stone), candleholder pressed class, acid matted 1988 Hackman, Iittala Photo credits: Iittala 7 Timo Sarpaneva Archipelago cast glass 1979 Iittala Photo credits: Rauno Träskelin 8 Timo Sarpaneva Marcel 2370 bowls mouthblown glass 1993 Iittala Photo credits: Rauno Träskelin 9 Aino Aalto Bölgeblick, tumbler vol 20 cl pressed class 1932 Karhula-Iittala Photo credits: Johnny Korkman 10 Harri Koskinen Uusi alue (New Area), Art Works Collection mouthblown, handcrafted glass 2009 Iittala Photo credits: Iittala 11 Iittala glassworks recycled glass 2020 Photo credits: Iittala 12 Oiva Toikka Tirri (Little Tern) mouthblown, handcrafted, 100 per cent recycled glass 2020 Iittala Photo credits: Iittala 13 Timo Sarpaneva i-line mouthblown glass 1956 Karhula-Iittala Iittala glassworks Photo credits: Rauno Träskelin 14 Iittala glassworks glass colour samples 2020 Iittala Photo credits: Johnny Korkman 15 Göran Hongell Säde tableware pressed glass 1938 Karhula-Iittala Karhula glassworks Photo credits: Johnny Korkman 16 Kaj Franck Kartio vase mouthblown glass 1958 Nuutajärvi, Iittala Photo credits: Johnny Korkman 17 Oiva Toikka Birds by Toikka, Korppi (Raven) mouthblown, handcrafted glass 1998 Nuutajärvi, Iittala Photo credits: Johnny Korkman 18 Yrjö Rosola Manalan tuli (Fire Of The Underworld), vase mouthblown glass, sandblasted 1936 Karhula-Iittala / Karhula glassworks