Paperwork – What drawings do

Paperwork explores the Architecture and Design Museum’s collection of architectural drawings. It asks: What do drawings tell us about the fundamental questions of architecture, and what is their role in architecture and culture overall? The drawings created on the architect’s drawing board and now held in the museum show how architecture is something more than just buildings. They show architecture as culture.

Drawings are the architect’s means for thinking and communicating. They are an important tool in the design and construction process, but they are also expressions of the visual culture of their time. As architecture and society change, drawings too change. They visualize the transformation of the built environment, but they also reveal much more. This exhibition guides viewers to see how drawings evince some of the key questions related to architecture: the relationship of the old and new and the place of the people in the city.

The exhibition and texts were produced by a group of art history students as part of a course at the University of Helsinki. During weekly workshops held in spring 2024, the students went through the Architecture and Design Museum’s architectural collections and studied basic questions related to both drawings and exhibitions. This exhibition sums up and displays their discussions and the discoveries made during the course.

Public space

Architecture defines the space around it. What is public space, and to whom does it belong? How is it created by architecture? How is it designed?

More than just buildings – also the space and its users

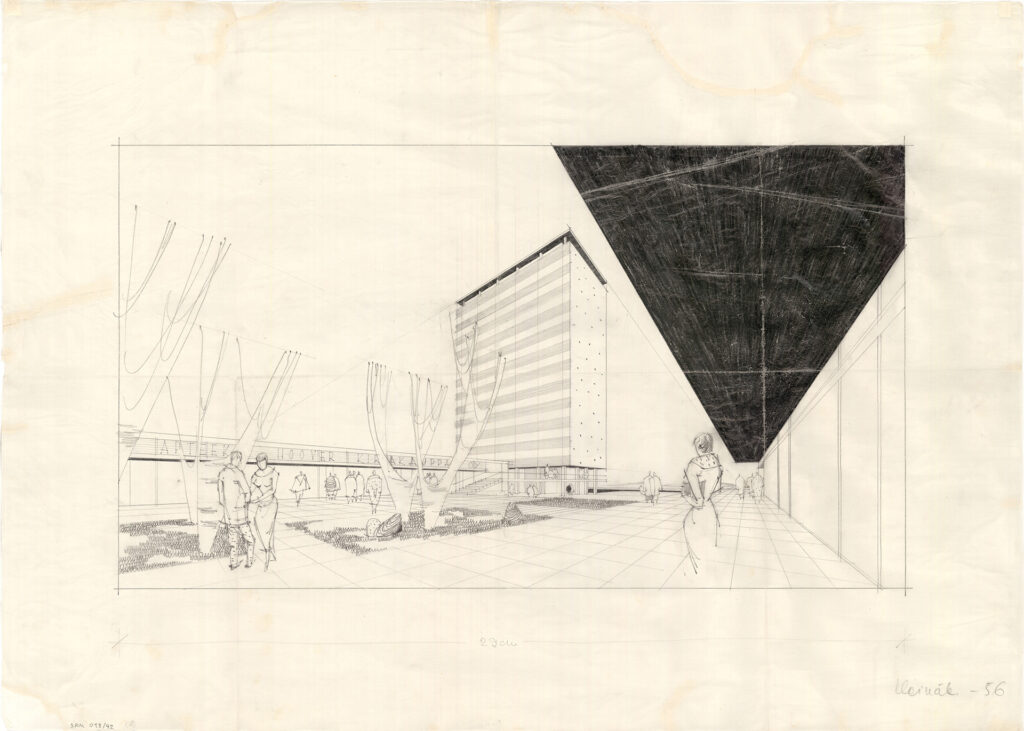

The foreground of this palatial bank designed by Gustaf Nyström and opened in 1898 is filled by its imagined fashionable clientele. The only visible blue-collar worker is consigned to the shadows of the building’s gateway. A more egalitarian spirit in expressed by Pauli Blomstedt’s 1930s drawing for the restaurant of the unrealized People’s Theatre (Kansanteatteri), presenting human figures as equally shaped angular silhouettes. Tapiola Commercial Centre from the 1960s is in turn presented as an inviting urban hub for running daily errands, with commercial and public services conveniently integrated on an equal footing. The drawings present not only architecture but also the social ideals of their era.

Gustaf Nyström (1856–1917). Union Bank of Finland, Aleksanterinkatu [street]. Perspectival drawing of the main elevation and street space,1897. Ink and watercolour on paper.

Pauli Blomstedt (1900–1935). Unrealized plan for the People’s Theatre restaurant in Hakaniemi. Perspectival drawing of the interior, circa 1932–1934. Ink and pencil on paper.

Aarne Ervi (1910–1977). Tapiola Commercial Centre. Early rendering of Tapiontori plaza in front of Tapiola Central Tower, circa 1955. Ink on paper. HUOM! luonnoksessa “heinäkuu 1956” jää paspiksen alle

Who are malls made for?

Juhani Pallasmaa’s plan for Itäkeskus shopping mall (1992) envisaged the main boulevard as a non-commercial space comprising services such as a children’s playground, exhibition space and indoor garden. When architects design malls, they often propose spaces where people can relax without spending money – but do these visions ever get off the drawing board? Teens and other low spenders are generally not welcomed in malls. The climate crisis raises new questions in this regard: What is the future function of shopping malls, and for whom should they be designed?

Erkki Kairamo (1936–1994). Itäkeskus shopping mall. Sketch of the indoor plaza in the main complex completed in 1984. Lead and coloured pencil and ink on paper.

Juhani Pallasmaa (1936). Itäkeskus shopping mall. Rendering of the extension added in 1992. Lead and coloured pencil on paper.

Juhani Pallasmaa (1936). Itäkeskus Boulevard (Bulevardi). Early layout sketches, 1987. Lead and coloured pencil, ink, and correcting fluid on diazotype.

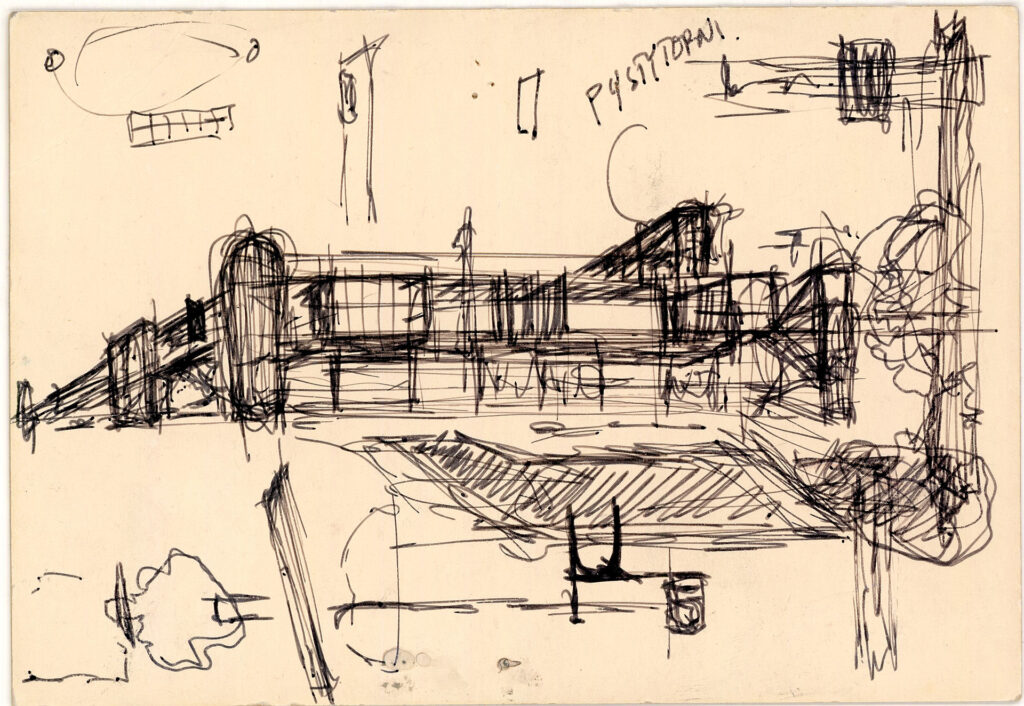

Sketches as part of the architect’s process

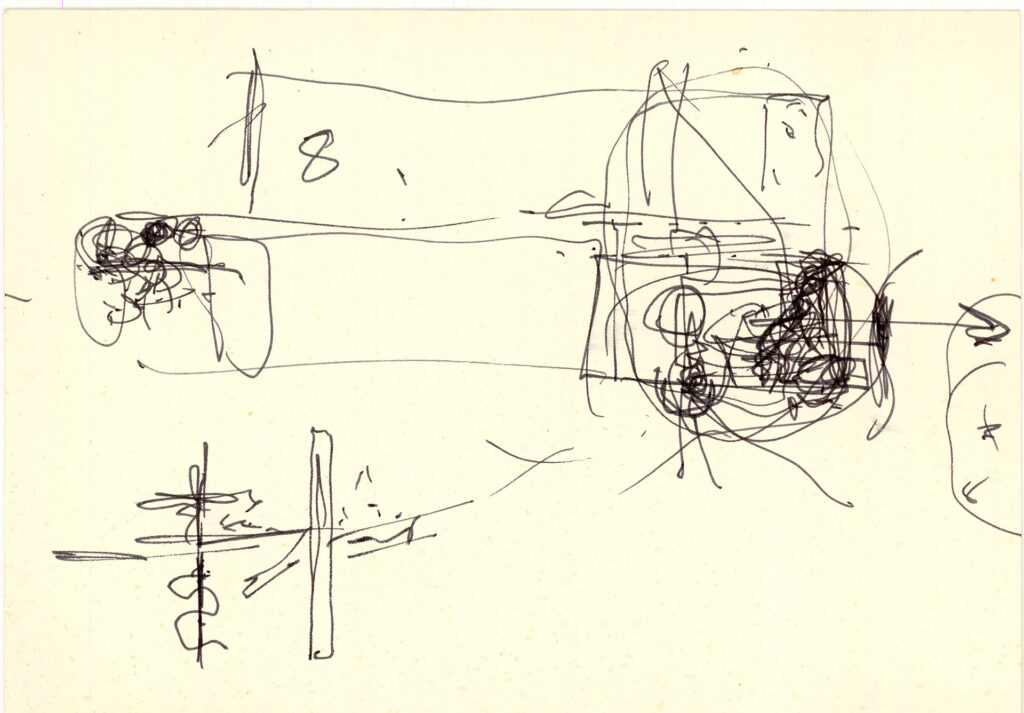

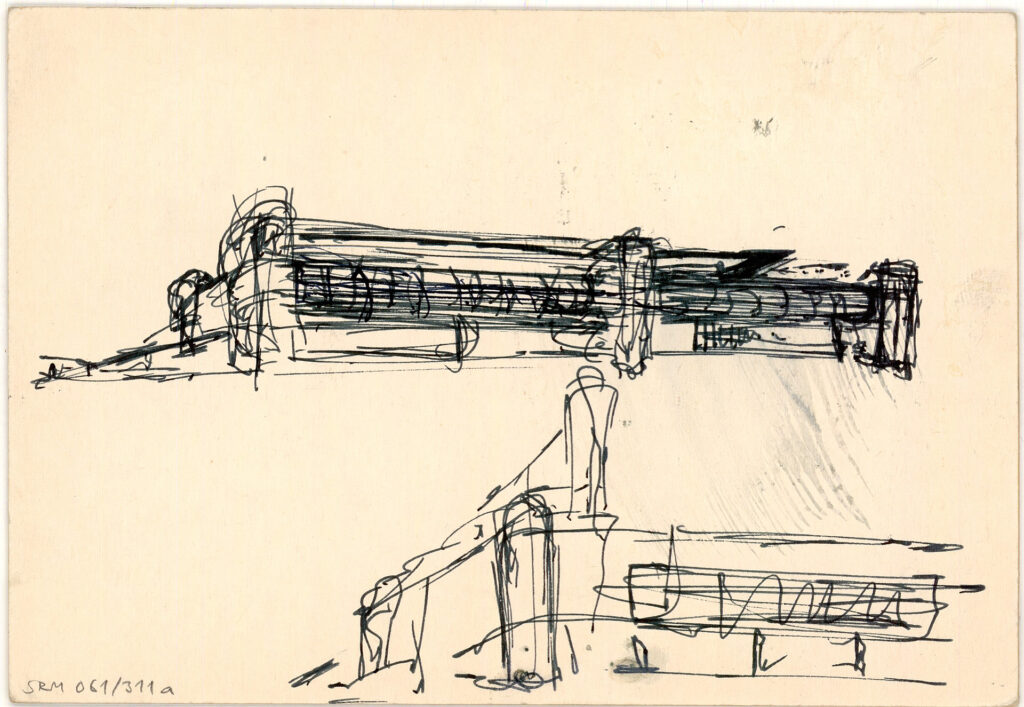

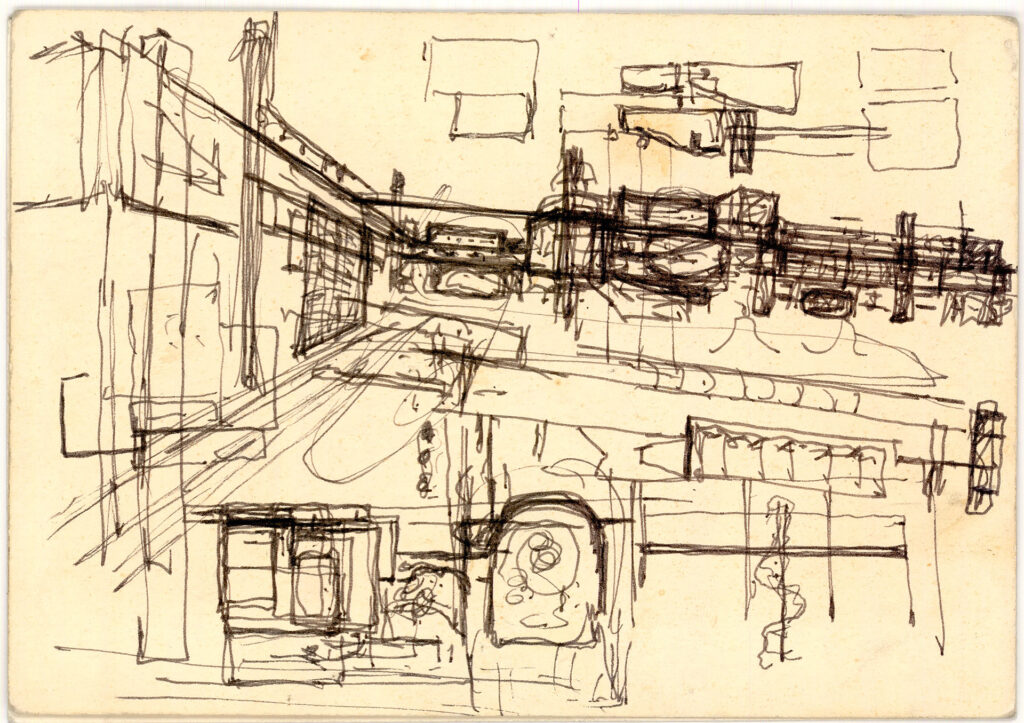

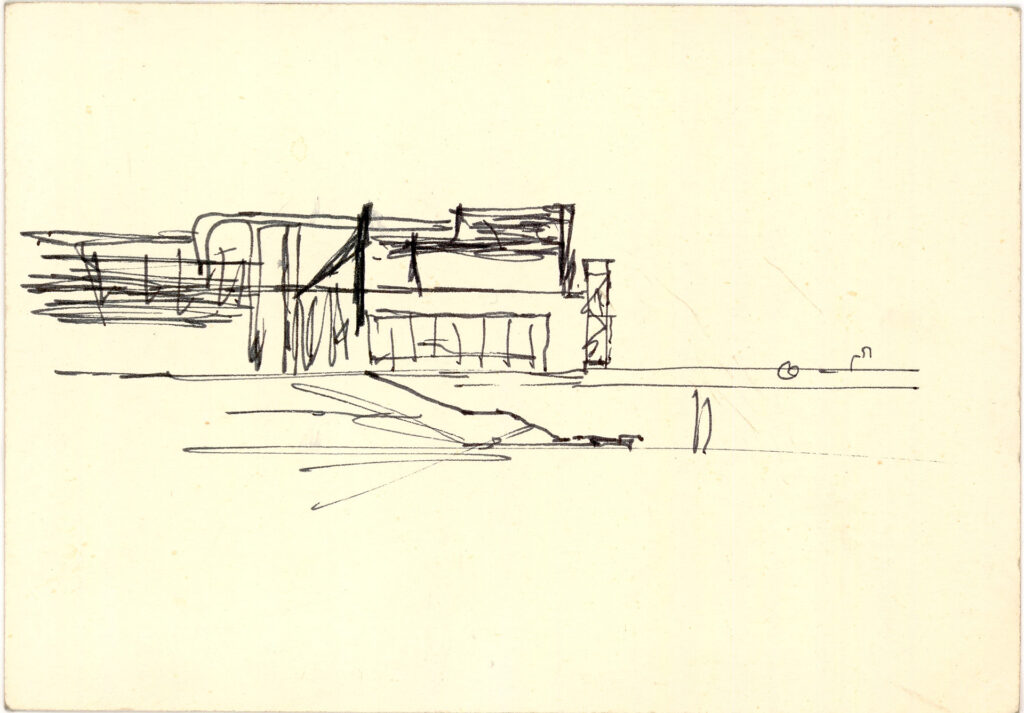

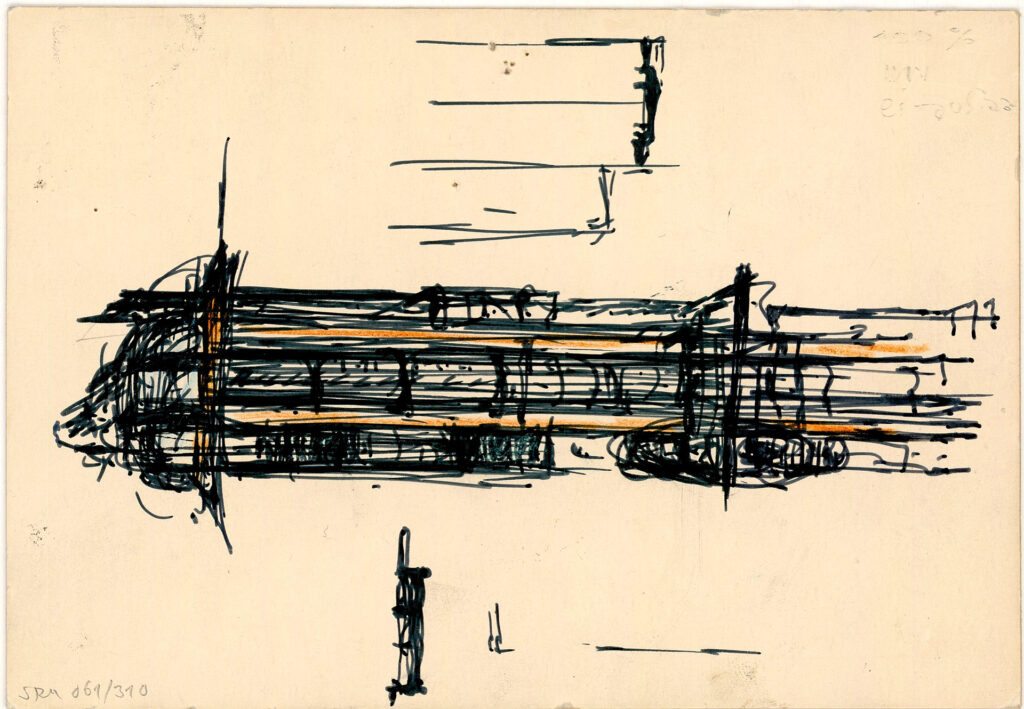

The design process never happens solely in the architect’s head. It involves manual labour, reiterations, experimentation and testing of new concepts, sometimes even wild ideas. Erkki Kairamo’s small-scale sketches on uniform cards suggest that the architect wanted to get his ideas down on paper as quickly and effortlessly as possible. He could then return to these dashed-off sketches as a source of fresh ideas in the later stages of planning.

Erkki Kairamo (1936–1994). Itäkeskus shopping mall. Series of sketches, circa 1980. Ink on cardboard.

Erkki Kairamo (1936–1994). Itäkeskus shopping mall. Series of sketches, circa 1980. Ink on cardboard.

Time

Architects plan for the future, but their designs also speak to the past and the present, weaving multiple temporal threads in a tapestry. What kinds of temporal layers exist in the city?

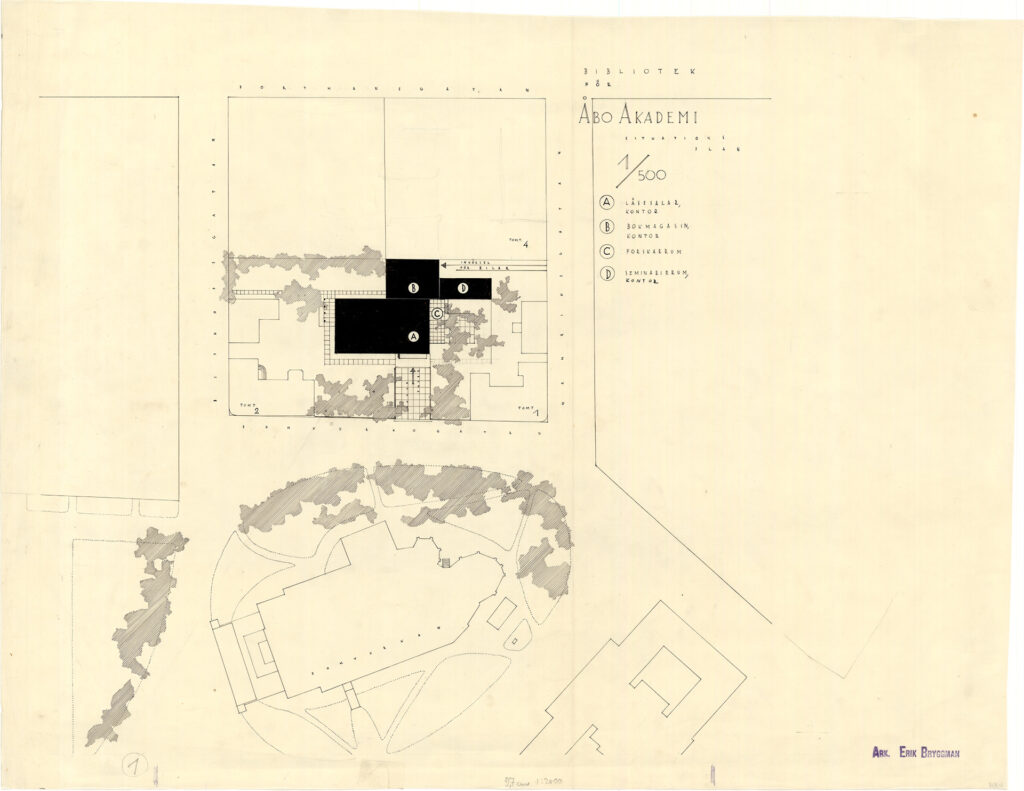

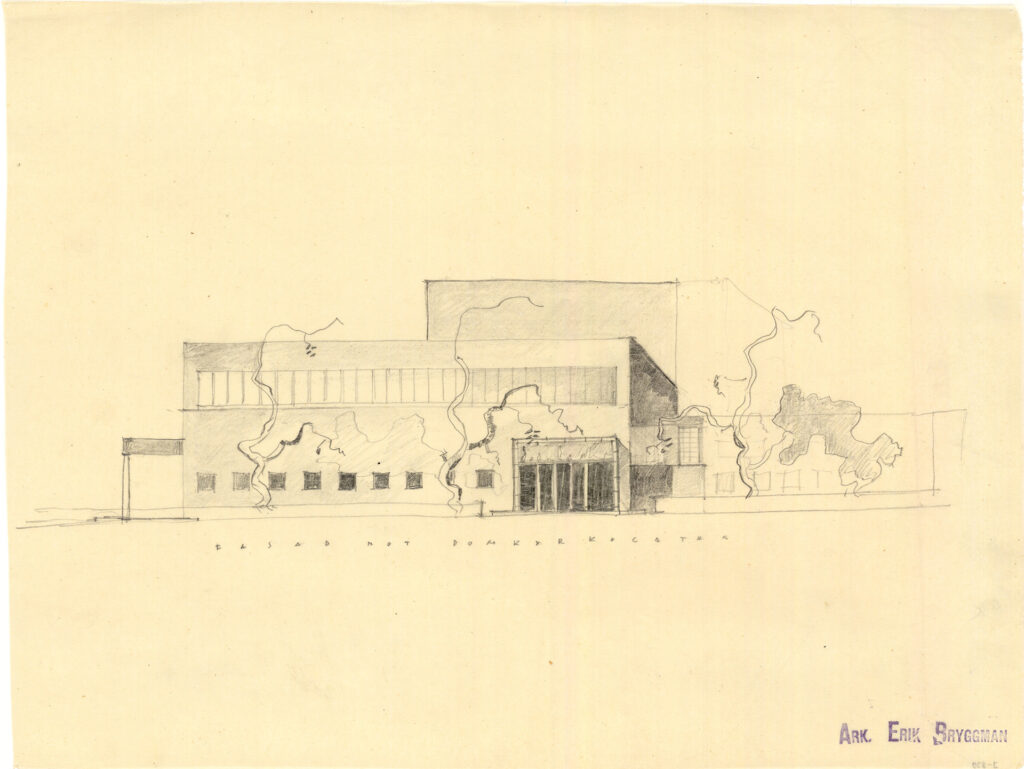

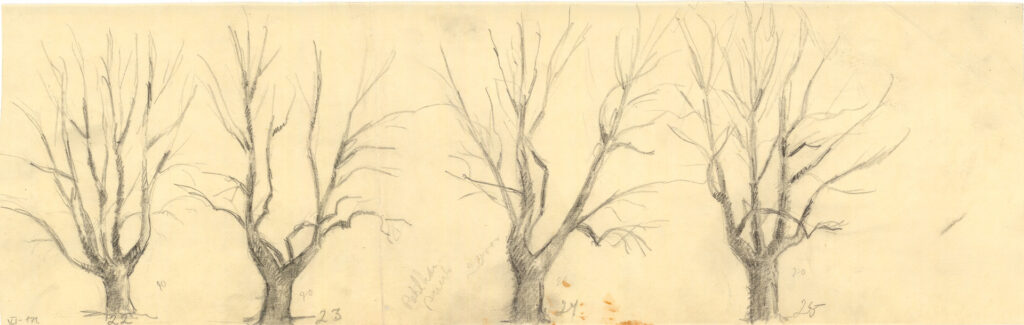

Natural and built layers of time in the city

Erik Bryggman’s drawings emphasize nature’s role as an element that creates harmony in urban spaces. The new building is organically integrated with its surroundings by vegetation, adding a new built layer to an urban landscape that has taken shape over a period of centuries. The lush old trees extend across the street from the cathedral to the library, subtly uniting centuries of architecture. The portraits of individual old trees highlight their importance – what is their role in the history of places and the temporal tapestry of the urban landscape?

Erik Bryggman (1891–1955). Åbo Akademi University’s Book Tower. Site plan of the library and Cathedral. 1934-1935. Ink on paper.

Erik Bryggman (1891–1955). Åbo Akademi University’s Book Tower. Site plan of the library and Cathedral. 1934-1935. Ink on paper.

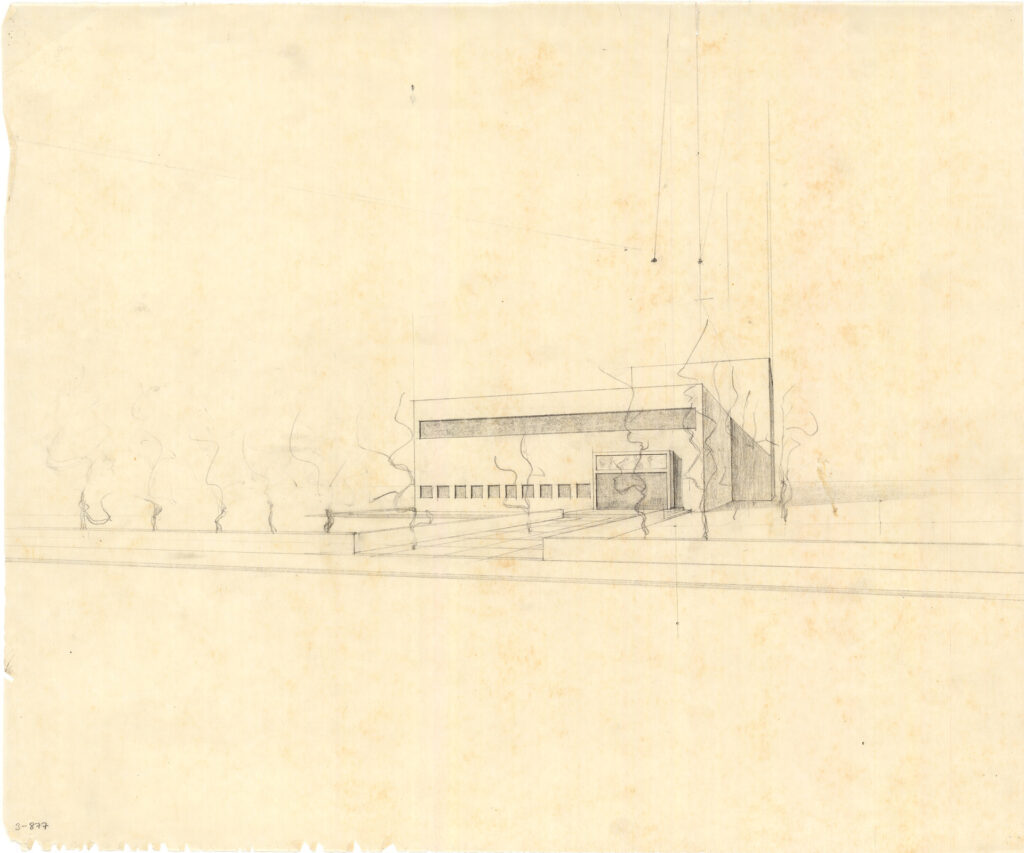

Erik Bryggman (1891–1955). Åbo Akademi University’s Book Tower. Studies for the main elevation. 1934. Pencil on sketching paper.

Erik Bryggman (1891–1955). Åbo Akademi University’s Book Tower. Studies for the main elevation. 1934. Pencil on sketching paper.

Erik Bryggman (1891–1955). Portraits of individual trees in Turku’s Porthaninpuisto Park done for the design of Pinella Restaurant.1940s. Pencil on sketching paper.

Erik Bryggman (1891–1955). Portraits of individual trees in Turku’s Porthaninpuisto Park done for the design of Pinella Restaurant.1940s. Pencil on sketching paper.

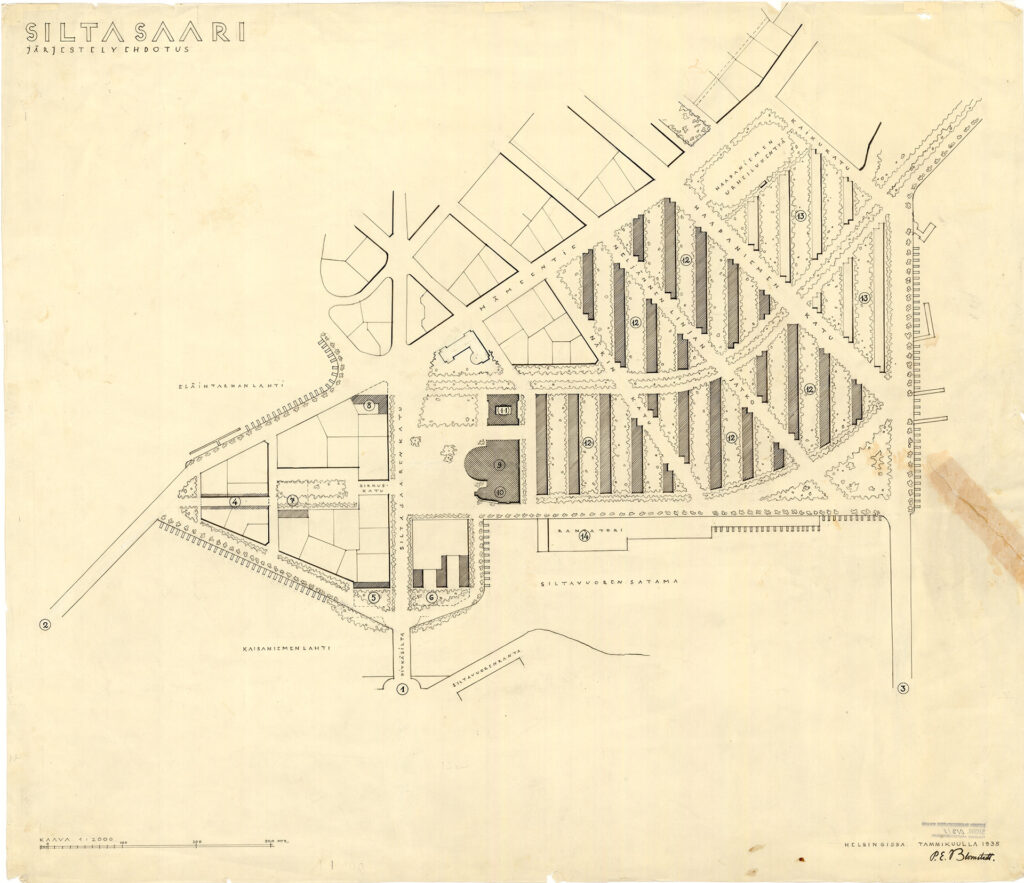

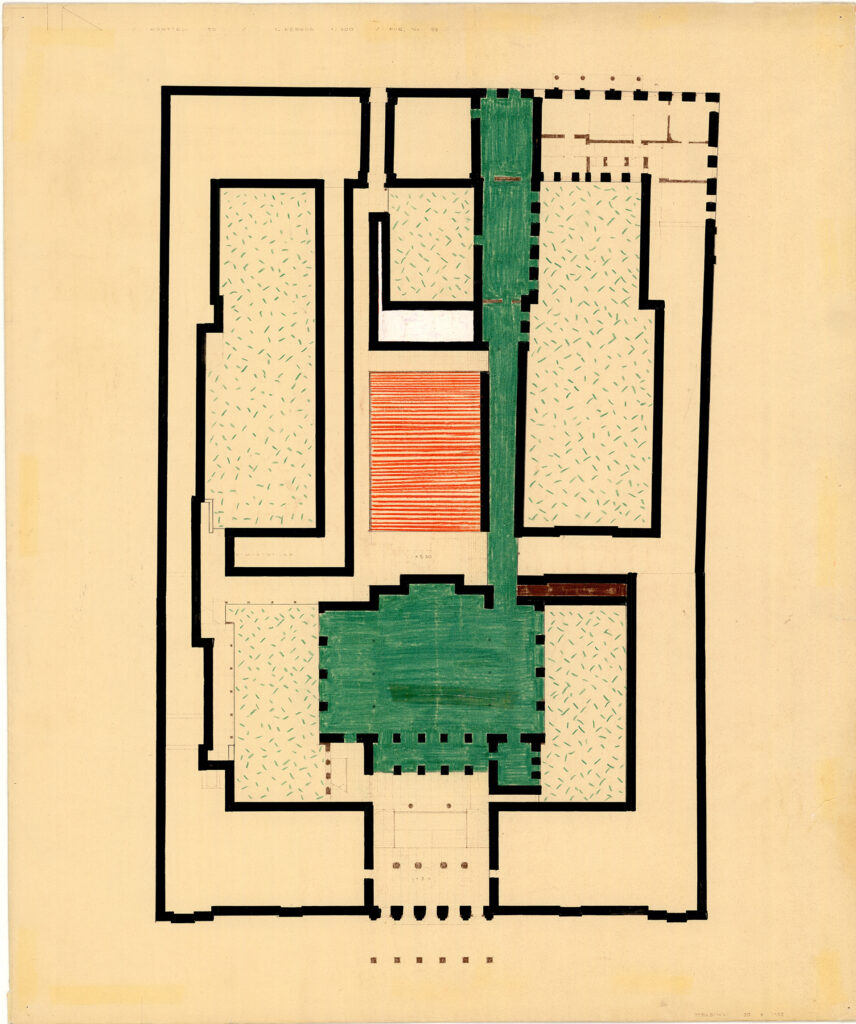

Pauli Blomstedt’s 1935 plan for the old industrial area of Siltasaari was largely unrealized. His proposal included new transport connections, commercial premises and modern residential buildings with abundant greenery. Blomstedt described his open green spaces as a conscious departure from dark, closed-off city blocks, marking a return to Helsinki’s Empire-era layouts and their harmonious balance between greenery and buildings. Blomstedt’s idea was to build tall, leaving plenty of open green spaces around the buildings.

Pauli Blomstedt (1900–1935), Plan for the Siltasaari area. Site plan. 1935. Ink on paper.

Pauli Blomstedt (1900–1935), Plan for the Siltasaari area. Site plan. 1935. Ink on paper.

Collage: Present meets future

These collages embed drawn buildings as part of a photograph, linking together the present and the future. By juxtaposing the present tense of the photographed reality and the future tense of the sketched idea, the collages reveal something essential about the nature of architectural drawings. They exist before the building does: they do not capture reality, but create it.

(photo)

Sigurd Frosterus (1876–1956). Sketches of a monumental building on the corner of Senate Square, 1920s. Pencil and coloured pencil on postcards.

(photo)

Marius af Schultén (1890–1978). Extension of the Nylands Nation clubhouse on Kasarmikatu [street]. Rendering, 1937. Gouache on photograph.

(photo)

Birger Brunila (1882–1979). Helsinki City Hall competition. Rendering, 1913. Pencil, coloured pencil and gouache on photograph.

(photo)

Pauli Blomstedt (1900–1935). People’s Theatre, Kasarmitori Square. Rendering, 1931. Pencil, coloured pencil and gouache on photograph.

Change

Architectural drawings show how the new relates to the old. What is proposed to be torn down, what altered, and what preserved?

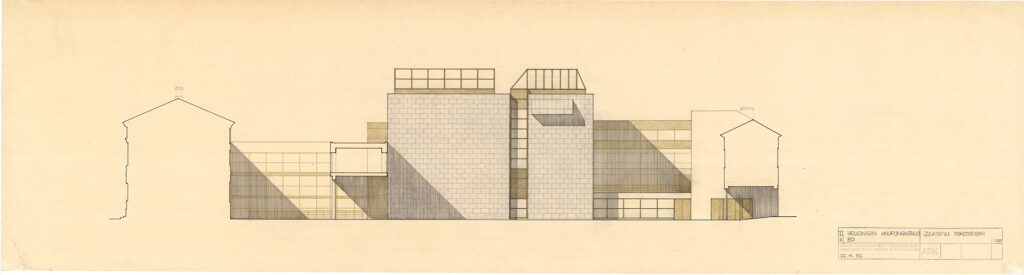

Subtle transformation: Drawing as a tool for thinking about space

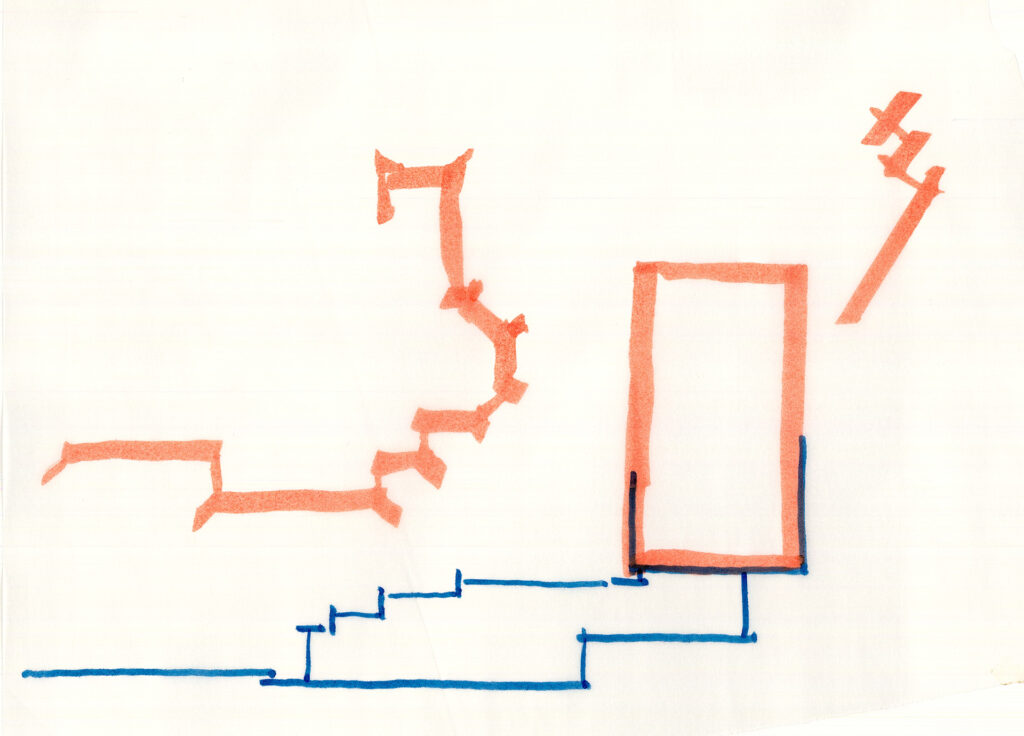

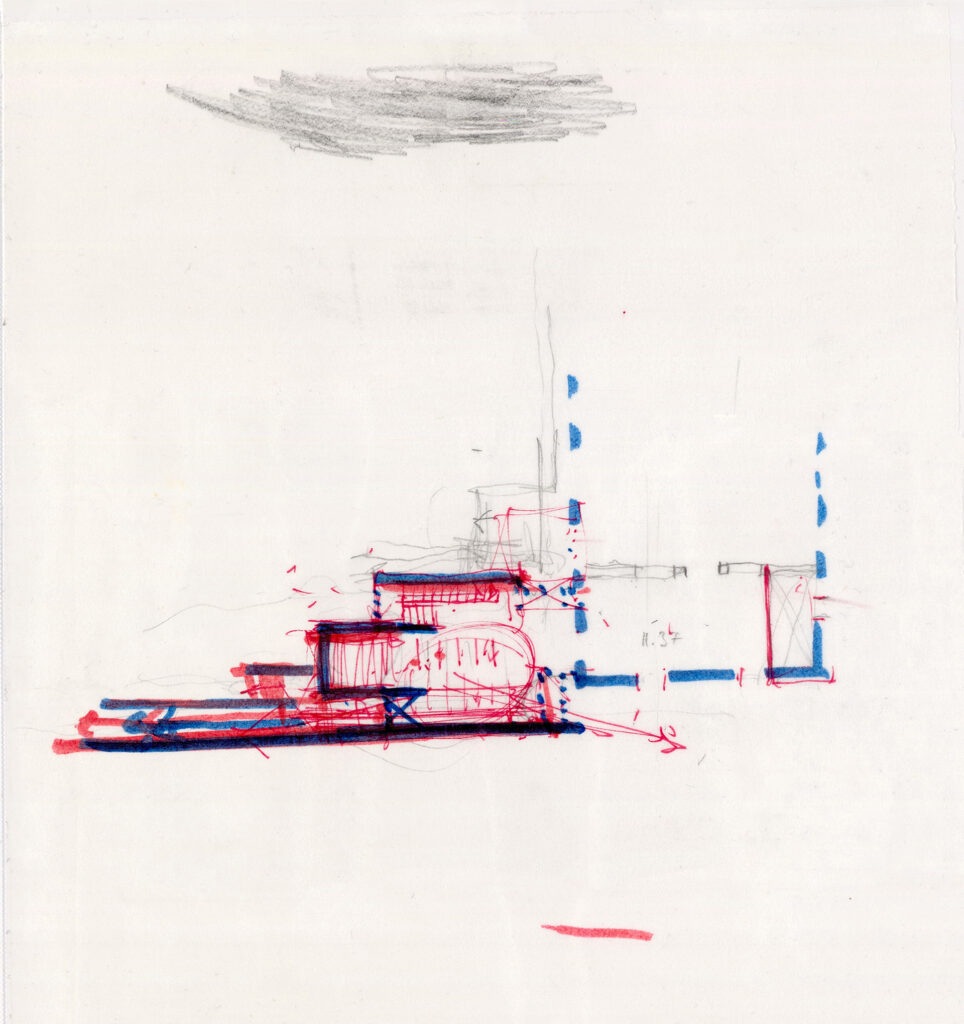

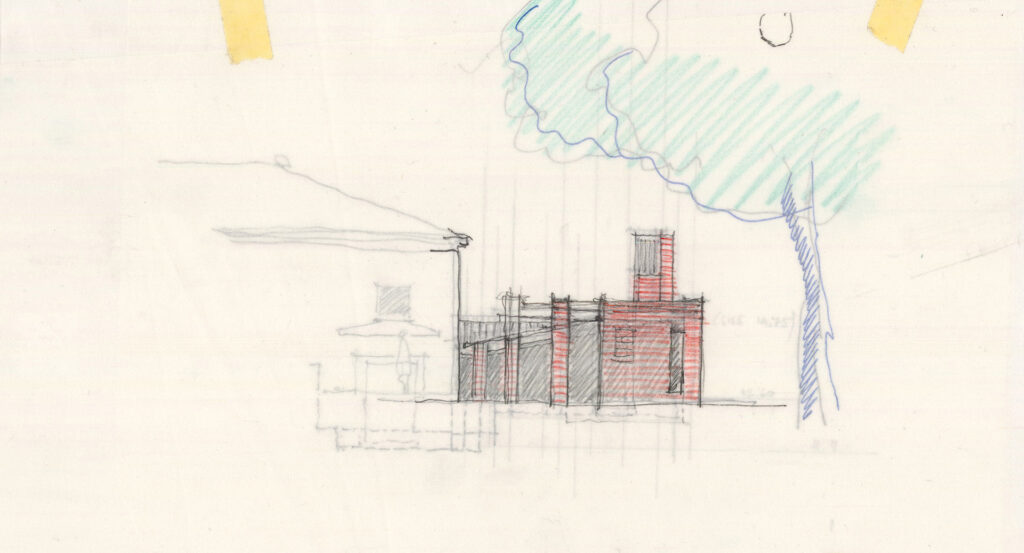

Juha Leiviskä’s studies for the 1997–2001 extension and transformation of Helsinki’s German Church reveal much about the architect’s process. For Leiviskä, sketching was a tool for thinking about space. Although the old church built in 1864 is understated in the sketches, the subtle new extension is respectfully integrated with the existing architecture. The restraint of Leiviskä’s approach is reflected by the thinness of the sketch paper, which is contrasted by the strong lines of the ink and felt-tip pen.

Juha Leiviskä (1936–2023). Extension of Helsinki’s German Church. Studies for the main elevation and floor plan, circa 1997–2000. Pencil and coloured pencil, felt-tip pen, and ink on sketching paper.

Juha Leiviskä (1936–2023). Extension of Helsinki’s German Church. Studies for the main elevation and floor plan, circa 1997–2000. Pencil and coloured pencil, felt-tip pen, and ink on sketching paper.

Juha Leiviskä (1936–2023). Extension of Helsinki’s German Church. Studies for the extension and its integration with the old church and rectory, circa 1997–2000. Ink marker, coloured pencil and felt-tip pen on sketching paper.

Juha Leiviskä (1936–2023). Extension of Helsinki’s German Church. Studies for the extension and its integration with the old church and rectory, circa 1997–2000. Ink marker, coloured pencil and felt-tip pen on sketching paper.

How far should conversions go?

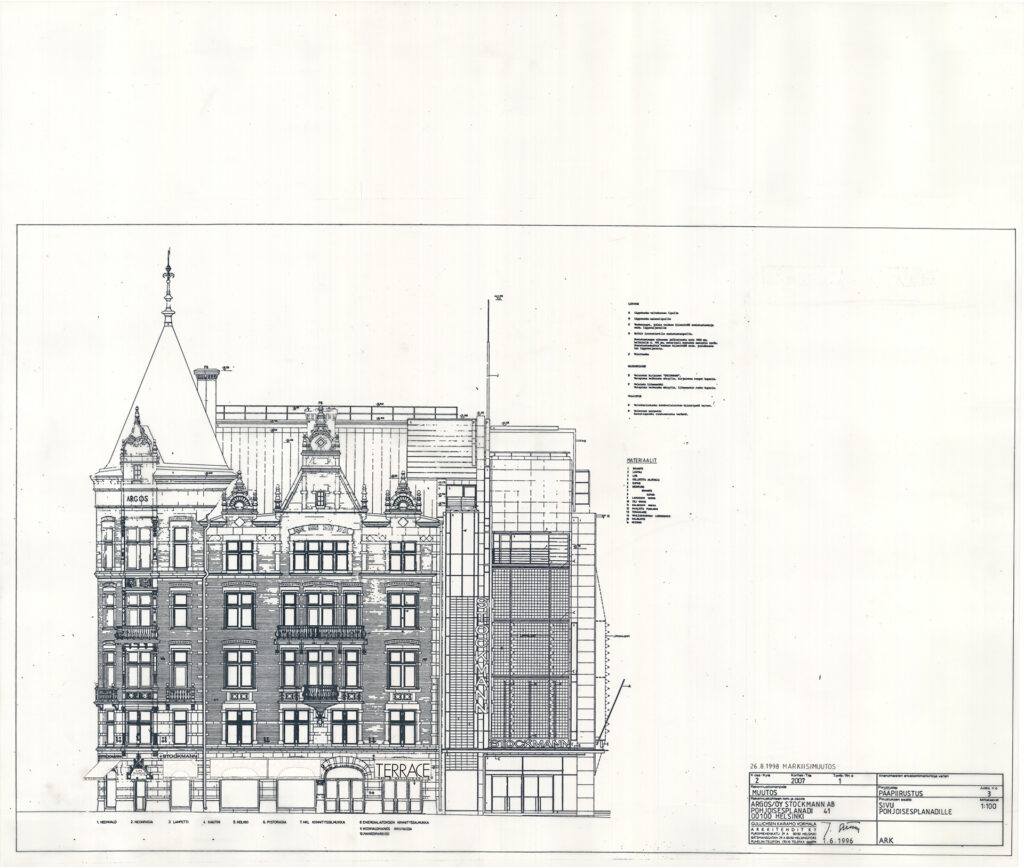

The fate of the Argos Building (1897) reflects a historic shift in Finnish architectural culture. The brick-built edifice forms part of Stockmann’s department store. It was to be demolished to make way for a new extension, but the plan faced strong public opposition. As a compromise, the façade was preserved and only the interior was rebuilt. The drawings present a precise document of the original façade details alongside new additions. They reveal the great effort involved in preserving the old and reimagining it as part of a new design.

Gullichsen Kairamo Vormala Architects. New awnings were added to the newly converted building, 1989. Correcting fluid on print.

Gullichsen Kairamo Vormala Architects. New awnings were added to the newly converted building, 1989. Correcting fluid on print.

(photo)

Matti Muoniovaara (Gullichsen Kairamo Vormala Architects), Argos Building. Detail drawings, 1980s. Pencil on sketching paper.

Drastic alteration on the pretext of reconstruction

Between 1962 and 1988, Helsinki City Hall underwent extensive reconstruction designed by Aarno Ruusuvuori. The early 19th century Empire block witnessed a radical transformation. Only the main façade and most important interior spaces were preserved while the rest of the complex ended up being fully rebuilt. Ruusuvuori’s dual approach to the project is reflected in his drawings. On one hand, he recognized the need to preserve the historically most valuable spaces, on the other, the architecture of the modernized spaces is drastically different from the existing building.

Aarno Ruusuvuori (1925–1992), Helsinki City Hall, first phase, 1960s. Floor plan. Ink, coloured pencil and felt pen on paper.

Aarno Ruusuvuori (1925–1992), Helsinki City Hall, second phase, 1980s. Inner court façade drawings. Ink and coloured pencil on diazotype print.

Aarno Ruusuvuori (1925–1992), Helsinki City Hall, second phase, 1980s. Inner court façade drawings. Ink and coloured pencil on diazotype print.

Drawings as a force of continuity

The Glass Palace building housing shops, a cinema and restaurants is a modernist landmark built in central Helsinki in the 1930s. The building was intended to be temporary, and the fact that it is still standing despite repeated threats of demolition speaks of its role as an emblem of continuity. The building was declared a protected

heritage site in the 1990s, and it underwent extensive renovations. The original drawings played a vital role in restoring its details – such as the flashing neon lights – to their former glory. The building stands as a reminder that the architecture we value changes over time – a truth often understood only when it is too late.

Viljo Revell (1910–1964), Niilo Kokko (1907–1975) and Heimo Riihimäki (1907–1962), The Glass Palace, 1934–1936. Façade and detail plans. Pencil on paper.

Viljo Revell (1910–1964), Niilo Kokko (1907–1975) and Heimo Riihimäki (1907–1962), The Glass Palace, 1934–1936. Façade and detail plans. Pencil on paper.

The collection and its blind spots

The Architecture and Design Museum’s collection holds the drawings of famous architects and offices. It reflects the way the field of architecture has been largely male-dominated throughout its history. Ways of making this exhibition more diverse was a subject discussed again and again during the course that produced this exhibition, but inclusivity was a challenge as the collection itself dictates what can be displayed.

This drawing by Elsi Borg was made to illustrate a new plan for central Helsinki designed by Oiva Kallio’s office. The central place in it is taken by a mother and child.

(photo)

Elsi Borg (1893–1958), Plan for Helsinki city centre by Oiva Kallio’s office, 1924. Rendering, 1926. Pencil, charcoal, ink and white crayon on paper.

Layers and connections

A city is a place of constant change. Its very idea revolves around the connections between people, nature, the built environment and different values. It is said that architecture takes place in between drawing and building, entailing both scholarly study and creative play. Drawings are the architect’s tools. They are a means of thinking, planning and communicating. Step in and see what kind of participation, interaction and deliberate transformation or renovation are proposed by drawings.