Known for her research and installations in museums, artist Caitlin Yardley questions the way we look at museums and the objects they display. In her upcoming exhibition Rhythm Without End at Helsinki’s Design Museum, Yardley considers the movement and influence of design objects, using ideas of circulation, rhythm and repetition to explore how they might simultaneously inhabit our world and be a lens from which to view it.

AA: Your installation Rhythm Without End has been developed in response to and will be shown alongside of the Design Museum’s permanent collections. Is there a particular reason why you feel so drawn to Finnish design and the Design Museum collection specifically?

CY: A number of my projects working with collections and archives have found their beginnings in a single object and my pursuit of that object’s origins and connections. Often that object leads me outside of the collection it is housed within and begins to link to wider narratives and associations. These outside journeys then become a useful lens through which to look back on the original object and form a new understanding of it and its position within the archive/collection/institution that contains it.

My work has been entangled with Finnish design for a number of years now. While this exhibition draws on an object designed by Aino Aalto, I came to Finnish design initially through Alvar Aalto and his iconic stool 60. I was researching in the archives of the Freud Museum in London and identified Aalto furniture in a photograph of Anna Freud’s consultation room. I later developed a project titled Mobile Composition on the art collection that moved through Maison Louis Carré, a house Aalto designed for a Paris art dealer. This sustained focus on Aalto eventually led to this project with the Design Museum but with the opportunity to move on. It was my initial intention of looking outward from Finland – using the international component of the collection to consider design objects more generally. However, I found the collection to have a far greater Finnish focus than I had presumed. Which makes sense! Finland has a significant design history and the collection primarily represents this prolific output in its holdings. This also reflects the nature and reality of how many museum collections are shaped – via donations and bequests with a smaller proportion coming from acquisition strategies. I have always been fascinated with the practices of biography, documentary and museology and the ideas of ‘completeness’ and ‘objectivity’ that we associate with them.

I immersed myself in the image archive and collection and spent time considering how the objects enter, exist and move through the world. The objects I was looking at were mainly Finnish in origin but my focus was on their wider international dialogue. One of circulation and continual movement.

The exhibition expands on this idea of the circular as formal and figurative concept, which became evident across disciplines and was encountered, in its multiplicity, within the holdings of the Museum. Spheres, cylinders, discs and rings. Objects revolving, spinning; made through rotation, formed on wheels, rolled or turned. Shapes that radiate and spiral.

AA: How do you consider the social aspect of collections in your work? Some people and narratives are not included in the collection scope and policies of museums and other institutions.

CY: The specificity of collections too often reflects the inequalities of their time and cultural context. The way they are presented today may make attempts to cover over or ignore these limitations – but omissions, absences, gaps and less visible narratives are increasingly being subjected to critical review. Archives are different in that they usually consist of both objects and ephemera in a less edited form – so there is often a less cautious paper trail and it is possible to unfold and reveal agendas and intentions in a less speculative way.

I find the idea of negative space really useful as a visual and conceptual way of thinking about history and absence through my work. Also, the use of fragmentation and repetition can make space for multiple subjectivities.

We know that history is often represented and arranged in singular, linear or fixed ways, and this is made evident through the endless use of limiting devices like the timeline, as well as the seductive theatre of display. I think it is important to underline what the institutional archive or collection is. It is essentially a container, and its volume and contents are often hard to define beyond what is made visible. This is where museum policy that promotes open access to independent research or actively initiates artist intervention and response is valuable.

AA: Collections tell us a lot about who we are and what we value as individuals, society and as a generation. By researching and rephrasing collections, are you trying to twist the narrative?

CY: I don’t believe there is ever a singular narrative. It is in aiming to pin down and fix a clear narrative that we obscure our vision and we return to limiting ideas of biography, memorial, legacy and the fetishised object. History should be continually redressed and revised, as we seek new understanding and increasingly wider perspectives.

I often try to employ peripheral vision when working with a collection or archive. I really like the idea of looking at something while simultaneously acknowledging its connection to something else. That something else – that connection – is perhaps not always a real or obvious connect; it is made simply because I can see or think about both things at once. This often leads me somewhere unexpected and new. As a working methodology, it also acknowledges that research is often partial and fragmented – but embraces that reality as something that can be used.

AA: Culture teaches us how to relate with objects. Can rearranging the objects create new relationships between the viewer, the artist, and the objects?

CY: Thinking about the object also as a kind of fragment is helpful. It can then be used to speak to its origins and context directly or taken outside of this and re-contextualised. There is a flatness to the convening of fragments that helps to retain a focus on the assembled nature of history. I try to work with media and processes in my practice that speak to this idea of assemblage and collision and hope that it provokes an engagement with history and ideas in a very particular way. For example, recent work drew on crazy quilting, a historical process of fragmented quilting that I used to create surfaces repeating the scale of a now dispersed collection of paintings. I see a relationship between quilting and painting, as both are concerned with the arrangement of material and surface, which can be used to assemble, reconvene and engage with history. They share pictorial and compositional problems and also generally a sense of domestic scale. Similarly, I also work with video editing for its relationship to a process of collage.

AA: Do you believe that your work could transform the meaning of objects? Is that important to you?

CY: I hope that my work speaks to ideas of meaning being always slippery and contingent. I am also aware of the limitations of my own research abilities and inability to at times overcome my own subjectivity – but I think the work reveals that too. I am not a historian and am trying to subject the art object and research process to the same ideas of assemblage as those found in the collection or archive.

I move about in terms of the medium I work in but come from beginnings in painting, which informs my approach. I am always interested in surface, perception and arrangement. Arrangement is increasingly a focus as the proximity and distance between things is where absence and gaps are located – the negative space. Which I see as a very generative space.

It is my intention to use these spaces to suggest a new way of thinking about the meaning of whatever it is I am looking at; sometimes this might transform the object – but only if the viewer comes with me on the journey.

AA: Do you personally have a passion for collecting things?

CY: I am certainly a collector but also very interested in the collections of others. I am deeply interested in the objects and materials that come to furnish our lives and how they connect the personal and local with much wider social histories and narratives.

There is also something really compelling, for me, in the repetition of a single object – I own twelve Alvar Aalto Savoy Vases, for example. They start to become almost sinister when you notice them recurring around a space.

AA: This idea of repetition is also investigated in Rhythm Without End, through your focus on Aino Aalto’s Bölgeblick glass plate from 1932. What motivated you to work with this specific design object?

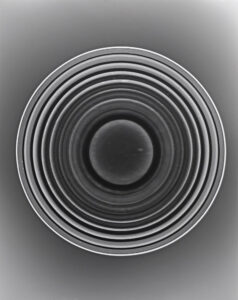

Aino Aalto’s Bölgeblick plate became a clear representation of my research logic. It is a circular glass design influenced by the concentric ripples that form on still water when disturbed. Produced in a centrifuge, its design also echoes its making and the way liquid glass behaves when subjected to high-speed revolution and gravitational force.

The plate also speaks to those ideas mentioned around absence and negative space – being currently out of commercial production. To work directly with it I first had to track it down. Some early examples were sent to me by a collector in Finland and some from New York, where they had been sold through the MOMA gift shop – possibly in the 80s. I used these plates to produce a series of photograms, a camera-less photographic process that creates a unique state print from direct contact between the object and the paper. In contrast to the speed and motion of the plate’s industrial production, photograms are made in a still and dark environment. A burst of light passes through the transparent object, exposing the paper. A photographic negative emerges following submersion and agitation in liquid developer, and the design is reinstated as a shadow of itself.

I am fascinated with the relationship between the art and design object. These objects come from different intentions of making and have different relationships to circulation. Rhythm Without End attempts to look at one through the other.

This interview is based on an interview by Athanasía Aarniosuo titled “Caitlin Yardley rephrasing collections,” originally commissioned by HIAP – Helsinki International Artist Programme, first published on the HIAP website on April 29, 2019. https://www.hiap.fi/caitlin-yardley-rephrasing-collections/

Text and interview:

Athanasía Aarniosuo

Translations:

Mauri Aarniosuo

Images:

Caitlin Yardley’s installation at Design Museum Helsinki (2021)

Published: 13.1.2021